Writing a disk-based key-value store in Golang

I’d been mulling around reading a computer science paper and implementing a project based on it. Distributed systems, Networking and Databases are some of the things that fascinate me a lot. However, I had been looking to implement a more approachable project to avoid getting inundated initially. And I happened to chance upon the Bitcask paper through Avinash’s project: CaskDB.

After giving a quick read of this reasonably short paper, I decided to write a Golang implementation of the same, as it looked like an exciting project. If you’re interested in checking out the complete project, checkout BarrelDB.

Bitcask is a disk-based key-value storage engine designed for fast read and write operations. It is mainly in production use by Riak (which is a distributed database) as one of the storage engines. Bitcask under the hood has a straightforward yet clever design. It writes to the file in an append-only mode. This means that writes are performed only by appending to the end of the file, thus avoiding the need to perform any random disk I/O seek.

Let’s look at various components of Bitcask:

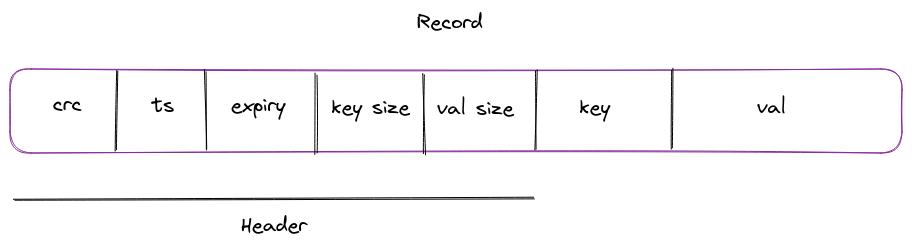

Format of the record#

- CRC: Stores the checksum of the value to ensure data consistency

- Timestamp: Timestamp in UNIX format, stored as int32.

- Expiry: If the record has an expiry defined, then the timestamp, in UNIX format, is stored as int32.

- Key Size: Size of the key in bytes

- Value Size: Size of the value in bytes

- Key

- Value

This additional metadata stored alongside the key/value is represented with a fixed-width header. Each field is represented as int32, so the total size of the header is 4*5 = 20 bytes. Here’s the code which encodes and decodes this record:

type Record struct {

Header Header

Key string

Value []byte

}

// Header represents the fixed width fields present at the start of every record.

type Header struct {

Checksum uint32

Timestamp uint32

Expiry uint32

KeySize uint32

ValSize uint32

}

// Encode takes a byte buffer, encodes the value of header and writes to the buffer.

func (h *Header) encode(buf *bytes.Buffer) error {

return binary.Write(buf, binary.LittleEndian, h)

}

// Decode takes a record object decodes the binary value the buffer.

func (h *Header) decode(record []byte) error {

return binary.Read(bytes.NewReader(record), binary.LittleEndian, h)

}The record is encoded in the binary format before storing it on the disk.

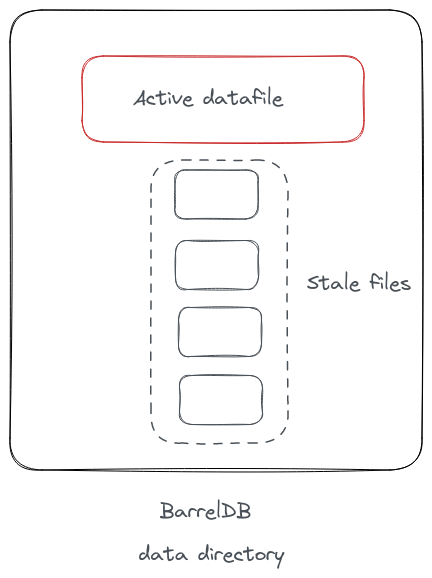

Datafile#

A “datafile” (term used for the DB file on disk) is an append-only record of all the write operations. An instance of Bitcask can have several datafiles. However, there’s only one “active” datafile. In BarrelDB, a goroutine runs in the background at regular intervals to check if the size of the active DB file has crossed the threshold and then rotates the active file. It appends this DB file to the list of “stale” data files. All the new writes only happen to the “active” data file, and the stale files are merged as a part of the “compaction” process (described later in the post).

Here’s how a datafile is represented:

type DataFile struct {

sync.RWMutex

writer *os.File

reader *os.File

id int

offset int

}It contains different handlers for writing and reading the file. The reason we have 2 file handlers instead of re-using the same one is that the writer is only opened in an “append-only” mode. In addition, since the active file can be rotated, the writer can be set to nil, ensuring no new writes ever happen on that file.

writer, err := os.OpenFile(path, os.O_APPEND|os.O_CREATE|os.O_WRONLY, 0644)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("error opening file for writing db: %w", err)

}

// Create a reader for reading the db file.

reader, err := os.Open(path)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("error opening file for reading db: %w", err)

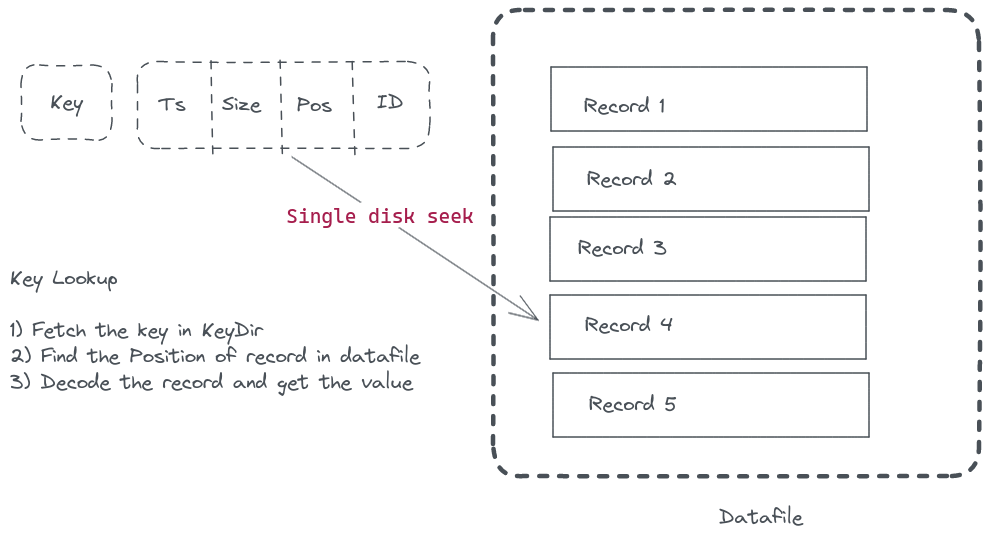

}KeyDir#

In addition to storing the file on disk, Bitcask also stores additional metadata, which defines how to retrieve the record. This hashtable is a map of keys with this metadata and is referred to as KeyDir. An important point to note here is that the value is never stored in this map. This makes it possible for Bitcask to handle datasets more significant than what the RAM can hold.

// KeyDir represents an in-memory hash for faster lookups of the key.

// Once the key is found in the map, the additional metadata, like the offset record

// and the file ID is used to extract the underlying record from the disk.

// Advantage is that this approach only requires a single disk seek of the db file

// since the position offset (in bytes) is already stored.

type KeyDir map[string]Meta

// Meta represents some additional properties for the given key.

// The actual value of the key is not stored in the in-memory hashtable.

type Meta struct {

Timestamp int

RecordSize int

RecordPos int

FileID int

}Here, RecordPos tells the record’s position offset (in bytes) in the entire file. Since the position of the record is stored in memory along with the key, the retrieval of the key doesn’t require more than a single disk seek. Bitcask achieves really low latency even with many keys in the database. A file system read-ahead cache also helps boost the performance and comes for free - no need to design a separate caching mechanism.

Compaction#

As we looked at previously, a datafile is simply an append-only sequence of writes. Any modification of the key is merely a new record appended to the datafile. KeyDir overwrites the entry of the key with the new metadata, which contains the new location of the record. Thus all reads will automatically return the updated value.

Deletes are handled similarly by writing a “tombstone” record for the key. When the user requests the key after it’s been deleted, BarrelDB can check whether that value equals the tombstone value and return an appropriate error.

As you would have guessed, our database will grow unbounded if we don’t perform any garbage cleanup. The datafiles need to be pruned for deleting expired/deleted records and merging all stale files in a single active file - to keep the number of opened files in check. All of these processes are together called “Compaction”.

Let’s take a look at how each of these compaction routine works under the hood:

Merge#

The merge process iterates over all the keys inside KeyDir and fetches their value. The value could come from a stale file as well. Once the new keys/values are updated, it writes them to a new active file. All the old file handlers are closed, and the stale files are deleted from the disk. The KeyDir is updated similarly since the new records live in a different position/file.

Hints File#

Bitcask paper describes a way of creating a “hints” file initially loaded in the database for faster startup time. This file is essential to bootstrap KeyDir after a cold startup. This avoids iterating over all data files and reading their values sequentially. In BarrelDB, gob encoding is used to dump the KeyDir map as a gob dump.

// generateHints encodes the contents of the in-memory hashtable

// as `gob` and writes the data to a hints file.

func (b *Barrel) generateHints() error {

path := filepath.Join(b.opts.dir, HINTS_FILE)

if err := b.keydir.Encode(path); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}During the startup, BarrelDB checks the presence of a .hints file, decodes this gob dump, and loads the data in KeyDir.

Removing expired keys#

A goroutine runs at a configurable interval to check if the value of the key has expired. If it has, it deletes the entry from KeyDir. During the following merge process, since this entry won’t be present in KeyDir, it’ll automatically be removed when the new datafile is created.

To check if the key has expired, a simple check, like comparing their timestamps in UNIX epoch format, is enough: time.Now().Unix() > int64(r.Header.Expiry).

Redis Server#

In addition to using BarrelDB as a Go library, I also implemented a redis-compatible server. I found tidwall/redcon as an easy-to-use library to create a Redis-compatible server for Go applications. All I’d do was wrap BarrelDB API methods and define handlers for SET / GET.

I was able to use redis-cli and connect to the BarrelDB server:

127.0.0.1:6379> set hello world

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> get hello

"world"Benchmarks#

You can check the repo for the actual benchmarks. However, I’d like to point out some inferences of the results from redis-benchmark.

First, let’s send 100000 requests to the server using 50 parallel clients. This command creates a unique key for each SET operation.

redis-benchmark -p 6379 -c 50 -t set -n 100000 -r 100000000

Summary:

throughput summary: 145985.41 requests per second

latency summary (msec):

avg min p50 p95 p99 max

0.179 0.016 0.183 0.207 0.399 1.727So, 140k requests per second is not bad at all for a disk-based KV. But the exciting thing to note here is that the performance is predictable even if you increase the load by increasing clients:

redis-benchmark -p 6379 -c 200 -t set -n 100000 -r 100000000

Summary:

throughput summary: 140845.08 requests per second

latency summary (msec):

avg min p50 p95 p99 max

0.718 0.224 0.711 0.927 1.183 5.775If we increase the number of requests (by 5x) as well, the throughput looks almost the same:

redis-benchmark -p 6379 -c 200 -t set -n 500000 -r 100000000

Summary:

throughput summary: 138350.86 requests per second

latency summary (msec):

avg min p50 p95 p99 max

0.748 0.056 0.711 0.879 1.135 63.135This magic is all because of the way Bitcask uses Log structured hash table (just append-only records for writing data). Even with a lot of records, all it has to do is to write to the end of the file, which avoids any expensive I/O operations.

Summary#

Overall, I am happy with BarrelDB implementation as I covered everything described in the paper. This project had excellent learning outcomes for me. I spent a lot of time coming up with a design for structuring different components and their API methods and handling all the edge scenarios during the compaction process. Although, full credit to Bitcask as it kept its design so elegant and minimal yet achieved some significant numbers in the benchmarks. This is also a reminder that simple need not necessarily mean less powerful.

I look forward to implementing a distributed KV store by adding support for multiple BarrelDB nodes connected via Raft. For now, gonna enjoy some chai and release this project to the WWW :)

Fin!